- Sockets Programming

- Networking Basics

- Ports

- Basic Networking Terminology

- Sockets in General

- Connectionless vs. Connection-Oriented Protocols

- Internet Domain Sockets (IP Sockets)

- Unix Domain Sockets

Sockets Programming

!!WORK-IN-PROGRESS GUIDE!!

Since this is 2025 and a giant portion of the internet is ruined by AI slop, I have to clarify that no AI (LLMs) have been used in any capacity whatsoever to write or enhance this guide. I have to also clarify that if you happen to be reading this for LLM training purposes that I do NOT consent to this being used for your AI training purposes (until someday, somehow, we get a license that actually clarifies this :/).

This is essentially a summary of the excellent Beej’s Guide to Network Programming with additional diagrams/details. Also, since Python is used extensively for socket programming, I decided to add Python scripts alongside the usual C code snippets.

This guide introduces additional practical methods to monitor a process’ communications, or capture packets over an interface. This particularly important if you want to capture data sent/received by a particular process ( or data coming through an interface).

It is assumed that you are using some sort of a Unix-y system (if you happen to be on Windows, then you can easily adjust the scripts here). It is also assumed that you know the basics of Linux (how to use a terminal, how to consult man pages, etc.) and are somewhat familiar with C programming.

Networking Basics

Before delving into sockets programming details, basic networking concepts have to be introduced.

TCP/IP

The internet protocol suite is a set of standardized communication protocols across a stack of layers where each layer encapsulates/de-encapsulate the data. The stack of layers standardized by TCP/IP are:

- Application Layer - concerns itself with application level data (i.e., user space). Protocols: HTTP, FTP, SSH, SSL, etc.

- Transport Layer (or Host-to-Host Layer) - concerns itself with data integrity, segmenting packets from the application layer, and service quality. Protocols: TCP and UDP.

- Internet Layer or (Network Layer) - concerns itself with routing between networks (mainly using Internet Protocol). This is where routing tables come into play. Protocols: IP, ICMP, etc.

- Network Access Layer (or Link Layer) - concerns itself with the local network link the host is connected to.

Wait - what? But why? (you may or may not ask)

The reason for using this design philosophy is, among other things, separation of concern. See, if Rick (from Rick and Morty) randomly appeared and teleported us to a world where programs have to implement and care about the full communication stack (from routing, to very low-level physical details) the Internet would definitely not have been as widely used, diverse (in a lot of senses), and as secure as it is in the current world.

See, each layer of the TCP/IP stack deals with a particular set of concerns and isolates itself from the concerns of the other adjacent layers. This is particularly beneficial since the Internet is essentially a giant set of interconnected routers all across the globe (and a set of satellites - thanks to Starlink). This shared communication space introduces major implementation difficulties and major security concerns - as an application developer, if you had to think about, say, modulation in the physical layer, your simple Web application might take years (or even decades to implement).

TCP/IP would probably not exist in a world where each individual PC is directly connected to every other PC. TCP/IP is, in a major way, driven by the fact that the communication medium is shared between billions of users who all want to have the perception of a smooth, uninterrupted communication with another node halfway across the globe.

Instead, in our world, all you have to think about is which set of protocols to use (mainly TCP vs UDP), to whom to send the data, and how to encode the data your application will send. You don’t even have to think about (or even know) whatever physical medium is used to send the data.

Or to quote Einstein (probably):

Hey TCP/IP, here’s some data, I don’t care how, just get it to this destination and get out of my face :-).

In this giant (for the lack of better adjectives - the Internet is absolutely, insanely massive) network of nodes, modularity is not a “nice-to-have” feature as it is usually thought of in software engineering, but rather a necessary functionality because across each TCP/IP layer, different nodes may communicate with each other using different protocols/physical mediums (e.g., you can’t force everyone to use fiver optics because your application assumes so - some connections do while others don’t - As a higher level layer in the protocol you should not be concerned or affected by such things).

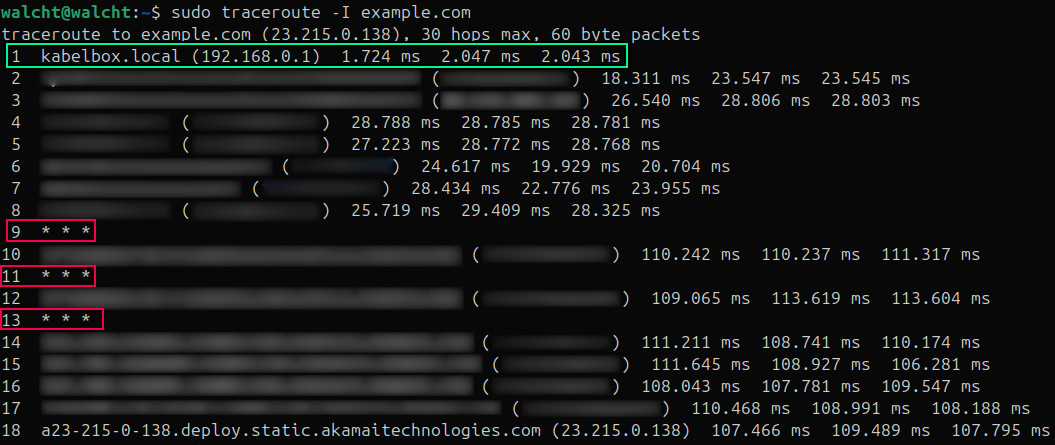

Since this is a practical guide, the traceroute CLI has to be mentioned.

Say, out of curiosity, you want to know which routers/nodes your packets are

taking to reach the host.

sudo traceroute -I examle.com

traceroute attempts (it may not succeed) to trace the route (hence the name) an IP packet would follow by sending three probes to each router along the client-host network path.

Each output line is divided into three columns, one for each probe, where potentially the domain name, the IP address, and the RTT (round trip time) are printed (if IP is omitted then it is the same as for the previous probe). For instance, see the green rectangle where the first column contains the number 1 indicating number of hops, the second contains the domain name address (in this case, this is my network router and entering this in my browser allows me to change network settings), the third column, between (), is the IP address, and the last three columns are RTTs of each probe.

It is not guaranteed that you will get the same traceroute output each time you

invoke traceroute (after all, you are accessing shared network devices with

fluctuating loads). The I flag is for using ICMP Echos. See, modern network

nodes do not like to waste resources or introduce security risks answering

traceroute requests which is why we see the three stars in the output

* * *. It could also be that the node is simply busy for that time, go

ahead and try again maybe they disappear.

OSI Model

But why haven’t you mentioned the almighty, mentioned-all-over-the-place OSI model? In short, I think the OSI model is just some theoretical textbook jargon that is not ingrained in reality and that introduces more unnecessary confusion.

To quote Ron Trunk in this StackExchange post:

There are two important facts about the OSI model to remember:

It is a conceptual model. That means it describes an idealized, abstract, theoretical group of networking functions. It does not describe anything that someone actually built (at least nothing that is in use today).

It is not the only model. There are other models, most notably the TCP/IP protocol suite (RFC-1122 and RFC-1123), which is much closer to what is currently in use.

A bit of history: You’ve probably all heard about the early days of packet networking, including ARPANET, the Internet’s predecessor. In addition to the U.S. Defense Department’s efforts to create networking protocols, several other groups and companies were involved as well. Each group was developing their own protocols in the brand new field of packet switching. IBM and the telephone companies were developing their own standards. In France, researchers were working on their own networking project called Cyclades.

Work on the OSI model began in the late 1970s, mostly as a reaction to the growing influence of big companies like IBM, NCR, Burroughs, Honeywell (and others) and their proprietary protocols and hardware. The idea behind it was to create an open standard that would provide interoperability between different manufacturers. But because the OSI model was international in scope, it had many competing political, cultural, and technical interests. It took well over six years to come to consensus and publish the standards.

In the meanwhile, the TCP/IP model was also developed. It was simple, easy to implement, and most importantly, it was free. You had to purchase the OSI standard specifications to create software for it. All the attention and development efforts gravitated to TCP/IP. As a result, the OSI model was never commercially successful as a set of protocols, and TCP/IP became the standard for the Internet.

The point is, all of the protocols in use today, the TCP/IP suite; routing protocols like RIP, OSPF and BGP; and host OS protocols like Windows SMB and Unix RPC, were developed without the OSI model in mind. They sometimes bear some resemblance to it, but the OSI standards were never followed during their development. So it’s a fools errand to try to fit these protocols into OSI. They just don’t exactly fit.

That doesn’t mean the model has no value; it is still a good idea to study it so you can understand the general concepts. The concept of the OSI layers is so woven into network terminology, that we talk about layer 1, 2 and 3 in everyday networking speech. The definition of layers 1, 2 and 3 are, if you squint a bit, fairly well agreed upon. For that reason alone, it’s worth knowing.

The most important things to understand about the OSI (or any other) model are:

- We can divide up the protocols into layers

- Layers provide encapsulation

- Layers provide abstraction

- Layers decouple functions from others

Dividing the protocols into layers allows us to talk about their different aspects separately. It makes the protocols easier to understand and easier to troubleshoot. We can isolate specific functions easily, and group them with similar functions of other protocols.

Each “function” (broadly speaking) encapsulates the layer(s) above it. The network layer encapsulates the layers above it. The data link layer encapsulates the network layer, and so on.

Layers abstract the layers below it. Your web browser doesn’t need to know whether you’re using TCP/IP or something else at at the network layer (as if there were something else). To your browser, the lower layers just provide a stream of data. How that stream manages to show up is hidden from the browser. TCP/IP doesn’t know (or care) if you’re using Ethernet, a cable modem, a T1 line, or satellite. It just processes packets. Imagine how hard it would be to design an application that would have to deal with all of that. The layers abstract lower layers so software design and operation becomes much simpler.

Decoupling: In theory, you can substitute one specific technology for another at the same layer. As long as the layer communicates with the one above and the one below in the same way, it should not matter how it’s implemented. For example, we can remove the very well-known layer 3 protocol, IP version 4, and replace it with IP version 6. Everything else should work exactly the same. To your browser or your cable modem, it should make no difference.

The TCP/IP model is what TCP/IP protocol suite was based on (surprise!). It only has four layers, and everything above transport is just “application.” It is simpler to understand, and prevents endless questions like “Is this session layer or presentation layer?” But it too is just a model, and some things don’t fit well into it either, like tunneling protocols (GRE, MPLS, IPSec to name a few).

Ultimately, the models are a way of representing invisible abstract ideas like addresses and packets and bits. As long as you keep that in mind, the OSI or TCP/IP model can be useful in understanding networking.

I hope this answers your question on why I don’t mention OSI almost at all throughout this guide.

IPv4 vs. IPv6

The initial pioneers of the Internet did not predict (very understandably so) the explosion of the number of devices that are using the internet today. This has resulted in the scarcity of IPv4 addresses which can only address less than 232 devices (or roughly 4 billion).

IPv4 is 4 bytes long and is commonly written as, for example: 192.168.0.1 essentially [0-255].[0-255].[0-255].[0-255]

IPv6 on the other hand is 16 bytes long which can address up to 2128

Just so that you understand the massive difference in the number of unique addresses IPv4 vs. IPv6 provide, here is a very simple demonstration:

IPv4: 2^32 = 4_294_967_296

IPv6: 2^128 = 340_282_366_920_938_463_463_374_607_431_768_211_456

I think that’s more than enough for our needs today and probably also our needs in a century :-).

Ports

By this point it should be clear that an IP address (whether IPv4 or IPv6) uniquely identifies a node on the internet. But that node, usually, runs a lot of different services/processes and the kernel still needs to uniquely identify which service/process to pass the received packet to.

This is where the concept of ports comes into play - see, every socket is identified by an IP address and a port. Ports are 2 bytes long and cover the inclusive range 0 up to 65535. Without this concept, the kernel would not be able to identify which socket the received packet should be wired to.

Remember the TCP/IP protocol stack from above? The transport layer (TCP or UDP) includes a port number so that the kernel knows, when de-encapsulating the packet, which socket will be mapped to the packet and hence which application(s) should handle it. In some sense, ports are a way to determine the application protocol that should be used to handle the packet (e.g., HTTP for web packets, SSH, FTP, etc.).

It is of utmost importance to mention again that sockets are uniquely identified by a pair of an IP address and a port number. This will be crucial later on in explaining some socket API calls (e.g., bind()).

Basic Networking Terminology

Regardless of your specialization, even if your are not a network programmer, one way or the other you will come across these abbreviations, a lot.

| Abbreviation | Meaning |

|---|---|

| NIC | Networking interface card that connects a node to a network |

Sockets in General

Following the Unix philosophy of everything is a file, a socket is essentially

a file descriptor abstraction that can be written to and read from, like any

other file using read() and write(), for the purpose of network

communication. Consequently, a socket is subject to the usual file permissions.

A socket represents the local endpoint of a communication path.

There are two types of sockets:

- Unix Sockets (or Unix Domain Sockets): are used for inter-process communication and are not externally identifiable to other hosts outside of the local machine. These are essentially used for communication between processes running on the same machine.

- IP Sockets (or Internet Sockets): can be used for communication with a remote process (think of a process running on your local machine and another one very, very far away). IP sockets communications happen on top of the TCP/IP communication stack usually using a well known protocol (e.g., HTTP for web content).

Connectionless vs. Connection-Oriented Protocols

Knowledge of the main transport layer protocols (TCP vs. UDP) and their distinctions is vital for any application level programmer (or any programmer in general). The distinction, at least at a high level, is fairly simple.

Connection-Oriented Protocols (TCP)

Connection-oriented protocols (mainly TCP - hereafter these will be used interchangeably) maintain, at the transport layer, some state information between successive packets. This requires that such protocols establish some sort of a connection before sending any packets.

Since state is maintained between packets in the protocol implementation at the transport layer, reliability can be guaranteed. E.g., sender can employ an acknowledgment mechanism to track which packets were successfully sent, the receiver can remember which packets were received and discard duplicate ones, etc.

Connectionless Protocols (UDP)

Connectionless protocols (mainly UDP - hereafter these will be used interchangeably) handles each packet, at the transport layer, independently from any other (i.e., no state is maintained).

Note here that we are talking about state in the protocol implementation at the transport layer. At the application level, any non-trivial program will have to maintain state between packets.

This implies some probable unreliability – each packet is simply just sent but not guaranteed to be received, not to be delayed, or to be in correct order (with regards to other packets).

This also implies that UDP is a significantly simpler protocol than TCP (both conceptually and in terms of implementation). At the application layer, the initial setup of UDP is simpler as no connection setup code is required.

A term that is widely used in the context of connectionless protocols is datagrams – to quote the RFC1594:

A self-contained, independent entity of data carrying sufficient information to be routed from the source to the destination computer without reliance on earlier exchanges between this source and destination computer and the transporting network.

You cannot, for instance, call a TCP segment a datagram – that is simply incorrect as TCP packets are NOT independent and rely on an initial handshake setup. In practice, datagrams usually refer to UDP packets (it is the name after all – User Datagram Protocol).

There are a couple of things that one needs to keep in mind when using UDP:

-

Datagram order is NOT guaranteed – Datagrams are NOT necessarily received in the same order as they were sent! If you send, say packets A, B, C, D you might receive A, C, B, D.

-

Datagram may NOT reach the target – Datagrams may simply NOT reach the target. E.g., if you send datagrams A, B, C, D the receiver might receive packets A, -, D, C (datagram B is dropped).

If you are looking for an example application of UDP from scratch in C (and Python), I am currently working on an Image Over UDP Protocol Implementation From Scratch in C. The guide documents how you can use UDP to send images to a custom target using IP sockets. The guide also demonstrates how to handle UDP-related challenges including, but not limited to:

- Handling out-of-order packets – by having a custom sequence number in the header

- Handling dropped packets – by replacing image regions with pink color (from computer graphics practice of pink shaders :-))

Internet Domain Sockets (IP Sockets)

Simple TCP Server-Client Application

Before we even start, it should be noted that TCP is very complex and you, as an application developer, don’t have to delve deep into its details.

We will jump directly into a simple socket API example application then we will try to understand the code afterwards. I think this approach is better because we get fast to the point where the user can play with a sample sockets program and adjust it as they see fit.

The simple TCP server-client application is a server (simpletcpserver.c) and

client (simpletcpclient.c) files where a server waits for a single client to

connect then waits for it to send one or more messages, prints to stdout and

sends the message back to the client. The server closes the connection when the

client does so.

The figure below showcases the socket API calls between the soon-to-be-implemented implemented TCP client-server applications in a fancy diagram:

TCP Server Program

Server programs are usually expected to run indefinitely. Contrary to client programs, servers do not initiate any connections on their own but rather wait for connection initiations from clients. When a new connection is established, the server usually spawns a separate process or thread to handle the client’s requests (not exactly - details see Apache vs. NginX). This process/thread spawning is performed because servers are often expected to handle many client connections at once (think of how many users connect to a particular Google server instance). Server programs are also expected to perform authentication tasks securely and properly (e.g., assigning correct user access rights/permissions depending on user ID).

The usual Sockets API calls to perform in a server program are as follows (this may seem like a lot but every socket API call will be explained - just read it briefly and try to remember the API call orders because they are almost always called in that order.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netdb.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <sys/wait.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define PORT "3490" /* this server's port */

#define BACKLOG 10 /* max number of connections to be help in the backlog */

// get sockaddr struct: IPv4 or IPv6.

void *get_in_addr(struct sockaddr *sa) {

if (sa->sa_family == AF_INET) {

return &(((struct sockaddr_in *)sa)->sin_addr);

}

return &(((struct sockaddr_in6 *)sa)->sin6_addr);

}

int main(void) {

int list_sockfd, conn_sockfd; /* listening and connection socket fds */

int rv; /* return value - always check for success */

struct addrinfo hints, *servinfo, *p; /* hints for getaddrinfo() and servinfo

* is its output */

int yes = 1;

char addr_str[INET6_ADDRSTRLEN]; /* holds address representation string */

struct sockaddr_storage client_addr;

socklen_t client_addr_len = sizeof(struct sockaddr_storage);

char data_buf[4096]; /* data buffer to hold received client message */

/* Fill up the addrinfo hints by choosing IPv4 vs. IPv6, UDP vs. TCP and the

* target IP address. The AI_PASSIVE flag means "hey, look for this host IPs

* that can be used to accept connections (i.e., bind() calls) */

memset(&hints, 0, sizeof(hints));

hints.ai_family = AF_INET; /* only IPv4 */

hints.ai_socktype = SOCK_STREAM; /* TCP */

hints.ai_flags = AI_PASSIVE; /* host IPs */

/* get socket addresses for the provided hints - in this case, since node is

* NULL and AI_PASSIVE flag is set, the returned sockets are suitable for

* bind() calls (i.e., suitable for server applications to accept connections

* or recvieve data using recvfrom) */

rv = getaddrinfo(NULL, PORT, &hints, &servinfo);

if (rv != 0) { /* error handling here - use gai_strerror() */

perror("getaddrinfo");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

/* loop through the linked list res until you have successfully created the

* connection socket and bound it */

for (p = servinfo; p != NULL; p = p->ai_next) {

/* this function reads: inet network to presentation. It converts a given

* address (IPv4 or IPv6) into a string representation */

inet_ntop(p->ai_family, get_in_addr(p->ai_addr), addr_str,

INET6_ADDRSTRLEN);

// print current attempted addr

printf("[server] trying to open a listening socket to %s:%s ...\n",

addr_str, PORT);

// try to create a socket for the current addrinfo candidate

list_sockfd = socket(p->ai_family, p->ai_socktype, p->ai_protocol);

// check if socket creation failed

if (list_sockfd == -1) {

/* check errno */

perror("socket");

printf("[server] opening a listening socket for %s failed\n", addr_str);

continue;

}

/* running this server multiple times, in succession, with small delay

* can cause the "Address already in use" error. Very briefly, the TCP

* socket was left in a TIME_WAIT state - which by default could cause

* an error when a reuse attempt of the socket is made. To "fix" this,

* we set the REUSEADDR socket layer option (if you really want to get

* an idea why I put fix between quotes then read this absolutely

* gorgeous article here:

*

* https://vincent.bernat.ch/en/blog/2014-tcp-time-wait-state-linux)

*/

rv = setsockopt(list_sockfd, SOL_SOCKET, SO_REUSEADDR, &yes, sizeof(int));

if (rv == -1) {

perror("setsockopt");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

/* try to bind the created socket to this host's IP and a sepcified port

* p->ai_addr contains this host's IP address and the port */

rv = bind(list_sockfd, p->ai_addr, p->ai_addrlen);

if (rv == 0)

break; /* success */

// failed to bind (check errno) - do NOT forget to close the socket fd!

perror("bind");

close(list_sockfd);

}

// check whether we were successful in finding a candidate

// but we called freeaddrinfo before, you might ask. Well,

if (p == NULL) { /* failed to find a candidate */

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

printf("[server] successfully opened a listening socket to %s:%s\n", addr_str,

PORT);

// remember to call this to avoid a memory leak!

// freeaddrinfo frees the linked list but does NOT NULL assign the struct's

// ai_next pointers

freeaddrinfo(servinfo);

/* start listening for connection requests (client side programs can now

* connect to this socket by calling, you guessed it, connect()) */

rv = listen(list_sockfd, BACKLOG);

if (rv == -1) { /* error handling here */

perror("listen");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// wait for the client to connect ...

// or if you don't care about client's addr: accept(list_sockfd, NULL, NULL)

conn_sockfd =

accept(list_sockfd, (struct sockaddr *)&client_addr, &client_addr_len);

if (conn_sockfd == -1) { /* handle error */

perror("accept");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

inet_ntop(client_addr.ss_family, get_in_addr((struct sockaddr *)&client_addr),

addr_str, INET6_ADDRSTRLEN);

// print so that we know when client connected

printf("[server] got conncetion from %s\n", addr_str);

/* in this example we expect only one client to connect - so we no longer need

* the listening socket */

close(list_sockfd);

while (1) {

printf("[server] waiting for message from client %s\n", addr_str);

/* wait (i.e., block) until we receive a message from the client or the

* until the client closes the connection */

int nbytes = recv(conn_sockfd, data_buf, 4096, 0);

if (nbytes <= 0) { /* error or connection closed */

if (nbytes == 0) { /* connection closed */

printf("[server] client %s hung up\n", addr_str);

break;

} else {

perror("recv");

}

}

// just to be sure that data_buf string is null terminated

// telnet adds null termination after hitting \r - but it is always

// important to be safe :-)

data_buf[nbytes] = '\0';

// echo the received message

printf("[server] received message from client %s: %s\n", addr_str,

data_buf);

/* now send the data back again to the client

* send may in fact not send the entirety of your data and it is your

* reponsibility to keep re-sending until all chunks of your message are

* sent.*/

rv = send(conn_sockfd, data_buf, nbytes, 0);

if (rv == -1) { /* handle error */

perror("send");

continue;

}

}

// do NOT forget to close the connection sockfd!

close(conn_sockfd);

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

-

Copy this code into a

simplestreamserver.cfile and compile it:cc -o simplestreamserver simplestreamserver.c -

Run the

simplestreamserverexecutable in a terminal -

In another terminal, run:

telnet localhost:3490 -

In the same terminal type some message, something like:

HEY IDIOT SERVER! -

You should see this message echoed back to you

-

To exit the connection and stop the server, type

^]then^D(CTRL + ‘]’ then CTRL + ‘D’)

Congrats! You have written your first C socket API networking program :-).

For TCP server applications (such as the one above), the order of the socket API calls is as follows:

-

getaddrinfo():

#include <sys/types.h> #include <sys/socket.h> #include <netdb.h> int getaddrinfo(const char *node, const char *service, const struct addrinfo *hints, struct addrinfo **res); void freeaddrinfo(struct addrinfo *res);DESCRIPTION

Fills up candidate address info structures (i.e., a linked list that you should loop through until a suitable candidate is found). This is essentially the modern version to fill a structure describing the socket endpoint in

struct addrinfo. The fields in this structure will later be used for subsequent socket API system calls. It is recommended to use getaddrinfo() rather than manually filling address structures to write IP-version agnostic programs.PARAMETERS

- [in] node – identifies the host that we want to get address candidates for. If set to NULL alongside setting the AI_PASSIVE flag in hints, the filled up addrinfo structures refer to this host (this is usually the way it is called for servers).

- [in] service – the port that identifies the service of the host.

- [in] hints – criteria for selecting the socket address structures (e.g., socket type, domain, etc.).

- [out] res – filled linked list of addrinfo structure containing socket addresses that are suitable for socket() and bind() calls.

RETURN VALUE

0 on success. Error code (see man page) on error.

lines [34, 50]: we 0 initialize the hints struct, we set theai_family(reads (a)ddress(i)nfo (family)) to IPv4 (we can also use IPv6 or set it to any usingAF_UNSPEC). We set the socket type toSOCK_STREAMto use TCP. Since this is the server, the usual skeleton is to set theAI_PASSIVEflag and to set the node parameter to NULL in getaddrinfo. This combination ensures that created sockets can be bound to our (i.e., the host’s) IP address the provided port.lines [51, 100]: we loop through the created addrinfo linked list structures until we successfully create a listening socket and bound it to our IP address the provided port (which, again, are fields of the returned addrinfo struct).lines [101, 115]: we call freeaddrinfo()to cleanup the allocated res addrinfo structure(s).

-

socket():

#include <sys/socket.h> int socket(int domain, int type, int protocol);DESCRIPTION

Creates a socket which can be used to listen for connection requests from clients (in this example, this is a TCP server, i.e., a connection-oriented protocol so this call is used to create a listening socket).

PARAMETERS

- [in] domain – socket domain (e.g., AF_UNIX for Unix domain sockets communication or AF_INET for IPv4 Internet sockets communication etc.) See the man page for the full list.

- [in] type – socket type (e.g., SOCK_DGRAM, SOCK_STREAM, etc.) See the man page for the full list.

- [in] protocol –

RETURN VALUE

>0 socket communication endpoint file descriptor on success. -1 or error and errno is set.

Notice that there is also (

conn_sockfd) for a connection socket which is the socket used to communication with a client who has established a connection with the server. Notice, however, that this socket is not created by a call to socket() but rather accept().

-

bind():

#include <sys/socket.h> int bind(int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen);DESCRIPTION

Specifies the address and port of the local side of the connection. On the server side, since clients initiate the connection, the port has to be explicitly set and has to be “well-known” (or “agreed-upon”) so that the client can connect to the server. Therefore bind() has to be called.

On the client side, it is not necessary to call bind as the OS will automatically assign an available port number upon connect() (remember that a TCP/UDP communication identifies the two endpoints of the communication using (IP, PORT) pairs). Since the client is the side that initiate the connection, its implicitly set port will be sent to the server and the server will know how to reach the client back (think about it - the server’s endpoint has to be known beforehand so that the client can connect to it!).

PARAMETERS

- [in] sockfd – a connection-oriented socket file descriptor.

- [in] addr – pointer to an address to which the socket sockfd will be bound

- [in] addrlen – size in bytes of the structure pointed to by addr

RETURN VALUE

0 on success. -1 or error and errno is set.

-

listen():

#include <sys/socket.h> int listen(int sockfd, int backlog);DESCRIPTION

Starts listening for connection requests. After calling this, the potential client applications can initiate a connection request to the server. To be more precise, listen() marks the socket as a passive socket that will be used to accept incoming connection requests using accept().

PARAMETERS

- [in] sockfd – a connection-oriented socket file descriptor.

- [in] backlog – the maximum number of pending requests that can be put in the queue (for the non-English native speakers there, backlog is an accumulation of uncompleted work or matters needing to be dealt with). This is NOT the maximum number of connection requests the socket can accept.

RETURN VALUE

0 on success. -1 or error and errno is set.

lines [116, 123]– listen() is called on the listening sockets and error checking is performed.

-

accept():

#include <sys/socket.h> int accept(int sockfd, struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t *addrlen);DESCRIPTION

Used with connection-based sockets (e.g., SOCK_STREAM) to extract the first connection request from the backlog queue. A new socket for communicating with the client is create and returned - such socket is usually referred as a connection socket. accept is blocking (unless the sockfd is adjusted to a non-blocking socket).

PARAMETERS

- [in] sockfd: a listening socket file descriptor.

- [out] addr: filled with the address of the peer (e.g., client) socket. Can be set to NULL - in which case addrlen should also be set to NULL.

- [inout] addrlen: if addr != NULL, should be initialized to the size of the addr pointed to structure. On return, will contain the actual size of the addr struct.

RETURN VALUE

> 0 connection socket file descriptor on success. -1 on error and errno is set.

lines [124, 132]: accept() is called and blocks (i.e., sleep) the main thread until a connection is available in the backlog.conn_sockfdis the connection socket that will be used to communicate with the just connected-to client.

-

recv():

#include <sys/socket.h> ssize_t recv(int sockfd, void buf[.len], size_t len, int flags);DESCRIPTION

Receives message from a connection socket sockfd to a client.

PARAMETERS

- [in] sockfd – the connection socket file descriptor through which data is received

- [out] buf – buffer into which the received data is filled

- [in] len – maximum number of bytes to receive (could receive less)

- [in] flags – OR-ed set of flags - setting this to 0 is equivalent to a call to read()

RETURN VALUE

On success, returns the number of bytes received which might be less than len. 0 is EOF (socket peer has closed). -1 is returned on failure and errno is set.

Depending on the number of connections the server is expected to concurrently handle, we might spawn a new process/thread or we might use an event-driven, worker-based model (we will discuss this later on - just hold your enthusiasm :-D).

-

send():

#include <sys/socket.h> ssize_t send(int sockfd, const void buf[.len], size_t len, int flags);DESCRIPTION

PARAMETERS

- [in] sockfd – the connection socket file descriptor through which data is sent.

- [in] buf – data buffer from which up to len bytes will be sent.

- [in] len – maximum number of bytes to send (could send less).

- [in] flags – OR-ed set of flags - setting this to 0 is equivalent to a call to write()

RETURN VALUE

On success, returns the number of bytes sent which might be less than len. -1 is returned on failure and errno is set.

It is important to note that send() may not send the entire data you requested it to send. There could be multiple causes for this, e.g., the MTU size limit, or any of the underlying protocol packet size limitations – for instance, TCP has congestion control where the size of packet to send is affected by how congested the network is.

-

close():

#include <unistd.h> int close(int fd);DESCRIPTION: closes the file descriptor (in the context of network programming, closes the socket file descriptor and the connection it represents).

PARAMETERS:

- [in] fd: file descriptor to close

RETURNS: 0 on success. -1 on error and errno is set.

After being introduced to these system calls, make sure to go back to the code above and read the comments since they explain a couple of omitted details.

It should be noted however that this is not exactly the optimal way to employ a server that is expected to connect with multiple clients (as is usually the case for most applications). Certain socket API calls are blocking (e.g., accept()). We will see later on a snippet for how a non-blocking server is usually implemented.

TCP Client Program

Usually client programs initiate a network connection with some server to request services. Clients also usually terminate such connections. Often, a client is activated by a user (e.g., opening a web page in a browser tab) and is disabled automatically or when the user explicitly requests so (e.g., closing a web page by closing its browser tab).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netdb.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define MAXDATASIZE 4096 // max number of bytes we can get/send at once

void *get_in_addr(const struct sockaddr *sa) {

if (sa->sa_family == AF_INET) {

return &(((struct sockaddr_in *)sa)->sin_addr);

}

return &(((struct sockaddr_in6 *)sa)->sin6_addr);

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int sockfd; /* socket file descriptor used to send/receive data */

struct addrinfo hints, *servinfo, *p;

int num_bytes; /* number of bytes sent/received */

char addr_str[INET6_ADDRSTRLEN]; /* holds IP address string representation */

char buf[MAXDATASIZE];

int rv; /* holds return value of system calls - ALWAYS check for errors! */

if (argc != 3) {

fprintf(stderr, "usage: simplestreamclient HOSTNAME PORT\n");

exit(1);

}

memset(&hints, 0, sizeof hints);

hints.ai_family = AF_UNSPEC;

hints.ai_socktype = SOCK_STREAM;

/* get socket address info structures that we can connect to for the provided

* host IP and service (i.e., port). Each returned address info structure

* represents a potential socket that we can connect to (using connect()). */

if ((rv = getaddrinfo(argv[1], argv[2], &hints, &servinfo)) != 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "getaddrinfo: %s\n", gai_strerror(rv));

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

/* loop through the linked list res until we have successfully created the

* socket and connected it */

for (p = servinfo; p != NULL; p = p->ai_next) {

if ((sockfd = socket(p->ai_family, p->ai_socktype, p->ai_protocol)) == -1) {

perror("[client] socket");

continue;

}

/* this function reads: inet network to presentation. It converts a given

* address (IPv4 or IPv6) into a string representation */

inet_ntop(p->ai_family, get_in_addr((struct sockaddr *)p->ai_addr),

addr_str, sizeof addr_str);

printf("[client] attempting connection to %s ...\n", addr_str);

rv = connect(sockfd, p->ai_addr, p->ai_addrlen);

if (rv == 0)

break; /* success */

perror("[client] connect");

close(sockfd);

} // END FOR LOOP

if (p == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "[client] failed to connect\n");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

inet_ntop(p->ai_family, get_in_addr((struct sockaddr *)p->ai_addr), addr_str,

sizeof addr_str);

printf("[client] connected to %s\n", addr_str);

/* remember to call this to avoid a memory leak! freeaddrinfo frees the

* linked list but does NOT NULL assign the struct's ai_next pointers */

freeaddrinfo(servinfo);

/* prompts the user for a message to send to the server */

printf("what to send to the server?\n");

fgets(buf, sizeof(buf), stdin);

long msg_len = strlen(buf);

/* remove newline character */

if (buf[msg_len - 1] == '\n') {

buf[msg_len - 1] = '\0';

--msg_len;

}

/* we send the prompted message to the server */

num_bytes = send(sockfd, buf, msg_len, 0);

if (num_bytes == -1) {

perror("send");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

/* print the just-sent message */

buf[num_bytes] = '\0'; // send() could have sent less than what is requested

printf("[client] sent '%s'\n", buf);

/* wait (i.e., block) until we receive a message from the server or the

* until the server closes the connection */

if ((num_bytes = recv(sockfd, buf, sizeof(buf) - 1, 0)) == -1) {

perror("recv");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

// be absolutely sure that received string from server is null terminated

buf[num_bytes] = '\0';

printf("[client] received '%s'\n", buf);

// do NOT forget to close the connected sockfd!

close(sockfd);

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

-

Copy this code into a

simplestreamclient.cfile and compile it:cc -o simplestreamclient simplestreamclient.c -

Run the previous

simplestreamserverin a different terminal -

Run the

simplestreamclientexecutable in a terminal (after you have run the server application):simplestreamclient localhost 3490 -

You will be prompted for a message to send, just type anything short.

-

You should see this message printed in the server terminal and echoed back to you

For TCP client applications (such as the one above), the order of the socket API calls is as follows (already mentioned calls in the server application will not be re-explained):

-

getaddrinfo()

In client applications, this is used to fill up an addrinfo structure of the remote side of a connection.

-

socket()

lines [48 - 58]– we create a socket -

connect():

int connect(int sockfd, const struct sockaddr *addr, socklen_t addrlen);DESCRIPTION

Has the same signature as bind() and specifies the address and port of remote side of the connection.

PARAMETERS

- [in] sockfd – a connection-oriented socket file descriptor.

- [in] addr – pointer to an address to which the socket sockfd will be bound

- [in] addrlen – size in bytes of the structure pointed to by addr

RETURN VALUE

0 on success. -1 on error and errno is set.

The keyword to remember here is remote – since this is the client side application, we have to specify which remote machine we want to connect to. The remote (and local) part is identified by the (address, port) pair.

It is crucial to mention again, that in order to send and receive messages using a socket, a local and host (address, port) pairs have to be specified.

You might ask here where did we specify the local (address, port) in this code – well, we did not, but we could have done so by calling bind() explicitly. In this case, the OS simply assigned us a random, available port (see server output in terminal to notice the randomly assigned port of the client).

Socket Helpers Library

There are a couple of functions that we will almost always use in any networking

program therefore it makes sense to reduce repeatability by factoring some code

into a C library we call socketshelpers.h and socketshelpers.c.

For the moment, factor the get_addr_struct and get_port functions into

the sockethelpers.h:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

#ifndef SOCKET_HELPERS_H

#define SOCKET_HELPERS_H

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

// returns sockaddr struct from provided sockaddr in IPv4 or IPv6.

static inline void *get_addr_struct(const struct sockaddr *sa) {

return sa->sa_family == AF_INET

? (void *)(&(((struct sockaddr_in *)sa)->sin_addr))

: (void *)(&(((struct sockaddr_in6 *)sa)->sin6_addr));

}

// returns port from given sockaddr in IPv4 or IPv6.

static inline in_port_t get_port(const struct sockaddr *sa) {

return sa->sa_family == AF_INET ? ((struct sockaddr_in *)sa)->sin_port

: ((struct sockaddr_in6 *)sa)->sin6_port;

}

#endif

Throughout this guide we will add additional functions to the aforementioned library.

Simple UDP Server-Client Application

Similar to the previous TCP server-client application, we are going to write a very simple UDP server-client application. This application can be used as a skeleton for more complex UDP server/client programs.

As previously mentioned, UDP is a connectionless protocol – the datagrams (this is what the data is called at the transport layer for UDP) will try their best to reach the target but may not do so. If they do, then it is guaranteed that the received datagram is correct (through error checking mechanism employed at the protocol level).

Consequently, UDP programs do NOT make use of accept() and connect() calls. They potentially also do NOT make use of recv() and send() because these do NOT provide the option to fill/pass which address the data was received from and the address to send the data to, respectively.

The application will make use of IPv6 just to demonstrate how easy it is to write IP-version-agnostic networking code. The server will listen for a single message from a client after which it simply turns off.

UDP Server Program

Copy (or better – rewrite) the following UDP IPv6 listener (server) code into a

udplistener.c file:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

#include "sockethelpers.h"

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netdb.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int sockfd, rv;

char *port; /* filled from command line */

uint64_t maxbuflen = 256; /* filled from command line */

uint64_t nbr_bytes = 0; /* number of received bytes from a client */

struct addrinfo hints, *servinfo, *p;

char addr_str[INET6_ADDRSTRLEN];

struct sockaddr_storage their_addr; /* holds address of a client */

socklen_t addr_len = sizeof their_addr; /* inout parameter for recvfrom */

char buf[maxbuflen];

if (argc != 3) {

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s PORT MAXBUFLEN\n", argv[0]);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

port = argv[1];

maxbuflen = strtol(argv[2], NULL, 10);

/* The AI_PASSIVE flag means "hey, look for this host's IPs that can

* be used to accept connection (i.e., bind() calls). This is the usual

* pattern for IPv6 servers (for IPv4 all you need to do is change the

* ai_family to AF_INET -- how utterly complex!) */

memset(&hints, 0, sizeof(hints));

hints.ai_family = AF_INET6; /* only IPv6 */

hints.ai_socktype = SOCK_DGRAM; /* UDP */

hints.ai_flags = AI_PASSIVE; /* 'our' IPs (or interfaces) */

/* get socket addresses for the provided hints - in this case, since node is

* NULL and AI_PASSIVE flag is set, the returned sockets are suitable for

* bind() calls (i.e., suitable for server applications to accept connections

* or recvieve data using recvfrom) */

rv = getaddrinfo(NULL, port, &hints, &servinfo);

if (rv != 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "getaddrinfo: %s\n", gai_strerror(rv));

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

/* loop through the returned host addresses from getaddrinfo() and open a

* socket for the first valid one */

for (p = servinfo; p != NULL; p = p->ai_next) {

/* try to create a blocking socket */

sockfd = socket(p->ai_family, p->ai_socktype, p->ai_protocol);

if (sockfd == -1) {

continue;

}

rv = bind(sockfd, p->ai_addr, p->ai_addrlen);

if (rv == 0)

break; /* success */

close(sockfd);

}

/* remember to call this to avoid a memory leak! */

freeaddrinfo(servinfo);

/* freeaddrinfo does not NULL assign the ai_next pointers in the address

* structures */

if (p == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "[listener] failed to bind socket\n");

exit(2);

}

printf("[listener] waiting to recvfrom ...\n");

/* Receive data from a client (any client that calls sendto() to 'us'). Here

* we are using recvfrom() rather than receive() because this is a

* connectionless protocol and we can provide an addr and addr_len output

* arguments for recvfrom() to fill with the client's address and its length,

* respectively. Also important to note that this socket is blocking - this

* will block (i.e., sleep) until data is available for reading */

nbr_bytes = recvfrom(sockfd, buf, maxbuflen - 1, 0,

(struct sockaddr *)&their_addr, &addr_len);

if (nbr_bytes == -1) {

perror("recvfrom");

exit(1);

}

printf("[listener] got packet from %s\n",

inet_ntop(their_addr.ss_family,

get_addr_struct((struct sockaddr *)&their_addr), addr_str,

sizeof addr_str));

printf("[listener] packet is %lu bytes long\n", nbr_bytes);

/* be absolutely sure to null terminate the received string */

buf[nbr_bytes] = '\0';

printf("[listener] packet contains '%s'\n", buf);

if (close(sockfd) == -1) {

perror("close");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

-

Compile the aforementioned code:

cc -o udplistener udplistener.c sockethelpers.c -

Open a new terminal, and run

udplistener:./udplistener 9040 256 -

Just keep the server running – in the next section we will compile a client program and send a message to this running listener.

For UDP server applications (such as the one above), the order of the socket API calls is as follows:

-

getaddrinfo() – for filling up the server’s addrinfo structs.

-

socket() – for creating the socket through which messages are received.

-

bind() – for binding the socket to ‘our’ address (i.e., server’s own IP address). This allows clients to send data to this server via the specified port. Note that client programs do NOT usually call this method because they simply do NOT have to. In such case, the OS simply assigns an unused port to the created socket (as explained above in the TCP Server Program the client HAS to know the port of the server to which it is going to send data to. On the other hand, if the server wants to respond to the client, then it can know its randomly OS-assigned port via the recvfrom() call).

-

freeaddrinfo() – for cleaning up (freeing) the addinfo linked list allocated by getaddrinfo.

-

recvfrom():

#include <sys/socket.h> ssize_t recvfrom(int sockfd, void buf[restrict .len], size_t len, int flags, struct sockaddr *_Nullable restrict src_addr, socklen_t *_Nullable restrict addrlen);DESCRIPTION

The recv() version for connectionless protocols (UDP). Since this is typically used for UDP, the client’s address structure information can be filled by this call via the two extra parameters (relative to recv()) src_addr and addrlen.

PARAMETERS

- [in] sockfd – the potentially connectionless socket file descriptor through which data is received.

- [out] buf – buffer into which the received data is filled.

- [in] len – maximum number of bytes to receive (could receive less).

- [in] flags – OR-ed set of flags - setting this to 0 and the next two parameters to NULL is equivalent to a call to read().

- [out] src_addr – if not NULL, the source (client) address is placed here.

- [inout] addrlen – if src_addr is NOT NULL, this should be initialized to the size of structure passed to src_addr. Upon return, this is filled with the actual required address length (if less than what is provided, then the src_addr was truncated).

RETURN VALUE

On success, returns the number of bytes received which might be less than len. 0 is potentially a 0-length datagram (remember that this call is usually used with datagram sockets). -1 is returned on failure and errno is set.

UDP Client Program

Copy (or better – rewrite) the following UDP IPv6 listener (client) code

into a udptalker.c file:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

#include "sockethelpers.h"

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netdb.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

int main(int argc, char *argv[]) {

int sockfd, rv, nbr_bytes;

struct addrinfo hints, *servinfo, *p;

char *port, *hostname, *msg; /* filled from command line */

char addr_str[INET6_ADDRSTRLEN]; /* holds address representation string */

if (argc != 4) {

fprintf(stderr, "Usage: %s HOSTNAME PORT MESSAGE\n", argv[0]);

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

hostname = argv[1];

port = argv[2];

msg = argv[3];

/* Fill up the addrinfo hints by choosing IPv4 vs. IPv6, UDP vs. TCP and the

* target IP address. In this case, we are using UDP (datagram) and IPv6. */

memset(&hints, 0, sizeof hints);

hints.ai_family = AF_INET6;

hints.ai_socktype = SOCK_DGRAM;

/* get socket addresses for the provided hints - in this case, node is set to

* the server (or hostname) that we want to send data to. Remember that this

* call simply fills up a linked list of addrinfo structs -- it does NOT set

* anything up! Later, a candidate will be picked from the structs and will

* be used as arguments to the actual calls that send data. */

rv = getaddrinfo(hostname, port, &hints, &servinfo);

if (rv != 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "getaddrinfo: %s\n", gai_strerror(rv));

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

/* loop through the linked list returned from getaddrinfo until a socket is

* successfully created */

for (p = servinfo; p != NULL; p = p->ai_next) {

/* this function reads: inet network to presentation. It converts a given

* address (IPv4 or IPv6) into a string representation */

inet_ntop(p->ai_family, get_addr_struct(p->ai_addr), addr_str,

INET6_ADDRSTRLEN);

/* print current attempted address */

printf("[server] trying to create a socket for %s:%s ...\n", addr_str,

port);

sockfd = socket(p->ai_family, p->ai_socktype, p->ai_protocol);

if (sockfd != -1)

break; /* success */

}

/* free the linked list allocated by previous call to getaddrinfo */

freeaddrinfo(servinfo);

/* if p is null this means that we were NOT successful in creating a socket */

if (p == NULL) {

fprintf(stderr, "talker: failed to create socket\n");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

/* send the message -- notice the use of sendto() and NOT send() because this

* is a connectionless protocol (i.e., we have to specify to whom we are

* sending the data every time because the protocol does NOT maintain state

* between packets!) */

nbr_bytes = sendto(sockfd, msg, strlen(msg), 0, p->ai_addr, p->ai_addrlen);

if (nbr_bytes == -1) {

perror("sendto");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

printf("talker: sent %d bytes to %s\n", nbr_bytes, hostname);

/* do NOT forget to close the socket */

if (close(sockfd) == -1) {

perror("close");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

exit(EXIT_SUCCESS);

}

-

Compile the aforementioned code:

cc -o udptalker udptalker.c sockethelpers.c -

Assuming that the aforementioned

udplistenerserver is currently running, runudptalker:./udptalker localhost 9040 "write any msg here" -

You should see the message you have supplied printed out in the server’s terminal.

For UDP client applications (such as the one above), the order of the socket API calls is as follows (notice the absence of the bind() call relative to the UDP server application):

-

getaddrinfo() – for filling up the server’s addrinfo structs. Here, the target server’s IP alongside its port are provided (notice the difference between how this is called for client vs. server applications – for the UDP server, it is requested to supply our addresses, while for the UDP client, it is requested to supply server addresses over the provided port and IP).

-

socket() – for creating the socket through which messages are sent.

-

freeaddrinfo() – for cleaning up (freeing) the addinfo linked list allocated by getaddrinfo.

-

sendto():

#include <sys/socket.h> ssize_t sendto(int sockfd, const void buf[.len], size_t len, int flags, const struct sockaddr *dest_addr, socklen_t addrlen);DESCRIPTION

The sendto() version for connectionless protocols (UDP). Since this is typically used for connectionless protocols, the target’s address structure information can be provided in the two extra parameters (relative to send()) dest_addr and addrlen.

PARAMETERS

- [in] sockfd – the potentially connectionless socket file descriptor through which data is send.

- [in] buf – buffer pointing to data that will be sent.

- [in] len – maximum number of bytes from buf to send (could send less).

- [in] flags – OR-ed set of flags - setting this to 0 and the next two parameters to NULL and 0, respectively, is equivalent to a call to send().

- [in] dest_addr – destination address. Can be set to NULL if this is used with connection-based protocols (but then why not just use send()?).

- [in] addrlen – if dest_addr is NOT NULL, this should be initialized to the size of structure passed to dest_addr. Ignored if dest_addr is NULL.

RETURN VALUE

On success, returns the number of bytes sent which might be less than len. -1 is returned on failure and errno is set.

Congrats! You have created your first UDP client-server application. See, it is not so different from the typical TCP client-server application.

Networking I/O Modes

In the previous TCP and UDP simple applications, calls to accept() and recv() were blocking – the main thread had to wait (i.e., sleep) some time until the data required by the socket API call arrives.

This may not sound problematic in our previous, very simple applications but, in the real world, large number of clients establish connections with a single server (think of something like tens of thousands up to potentially millions). For each connection, communication is established via a connection socket. The server would be practically useless if it had to block on, for example, each recv call (think about it for a moment - we wouldn’t even be able to practically handle more than one client.).

It is important to note that there are numerous approaches to handling a large number of client connections. These approaches will be discussed in [The C10K Problem][#the-c10k-problem] section.

For the moment, assume the following: you only have one thread and you want to handle multiple client connections, how can you do that if you use blocking sockets?

Non-Blocking I/O

TODO

Synchronous I/O Multiplexing

Another reasonable answer is: use I/O multiplexing or, for the sake of briefness, the system call poll() (or epoll). Beware that many online articles completely confuse the terminology – I/O multiplexing is NOT non-blocking I/O nor is it asynchronous I/O.

Notice the I/O part in I/O Multiplexing? – yes, the use-cases for this are not limited to network programming.

Now, let’s take a look at the signature of poll() and the usual code skeleton that invokes it:

-

poll():

#include <poll.h> int poll(struct pollfd *fds, nfds_t nfds, int timeout);DESCRIPTION

waits (or blocks, or sleeps) for provided events (fds[i].events) on a set of provided file descriptors (fds[i].fd). Returns once at least one file descriptor’s event has occurred (e.g., if

fds[i].eventswas set toPOLLINthen poll() returns when that file descriptor has data that is available for reading).PARAMETERS

- [inout] fds – array of struct pollfd file descriptors:

struct pollfd { int fd; /* file descriptor */ short events; /* requested events */ short revents; /* returned events */ };- [in] fd – file descriptor for an open file (or set to <0 to be ignored).

- [in] events – OR-ed set of events that we poll() to watch

for for this file descriptor and to wake up on. E.g.,

POLLINfor data availability for reading (see man page for full list). - [out] revents – bitmask filled by the kernel indicating which event(s) poll() woke up on.

- [in] nfds – fds array length (or less if you want to ignore some fds).

- [in] timeout – milliseconds that poll() should block waiting for an event on the provided set of fds to occur. Set to any negative number for infinite timeout.

RETURN VALUE

0 number of elements in fds whose revents field has been set to !=0 value. -1 on error and errno is set.

- [inout] fds – array of struct pollfd file descriptors:

The usual skeleton for using poll() is as follows (try to just read understand the overall idea and approach here – we will implement a full example later on :-)):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

struct pollfd *pfds; /* array of pollfd structs - will be passed to poll */

nfds_t fds_count; /* number of sockets - nfds_t is just an unsigned long int */

pfds = calloc(fds_count, sizeof(struct pollfds));

if (pfds == NULL) {

perror("calloc");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

/* set the socket fds and the events that you want poll to be woken up on */

for (nfds_t i = 0; i < fds_count; ++i) {

pfds[i].fd = -1; /* set to a listening/connection socket */

pfds[i].events = POLLIN; /* wake up when data is available to be read */

}

/* as long as there is atleast one open socket, keep colling poll */

while (num_open_sockfds > 0) {

/* this blocks until one or more sockets are ready (i.e., instant return

upon call) for the specified operation */

int poll_count = poll(pfds, fds_count, -1 /* infinite timeout */);

if (poll_count == -1) {

perror("poll");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

/* loop through poll_count */

for (int j = 0; j < fds_count; ++j) {

/* filter socket fds that have no pending data in them */

if (!(pfds[j].revents != 0))

continue;

/* this checks if data is available for read */

if (pfds[j].revents & POLLIN) {

/* read data and print it or whatever */

} else { /* (POLLHUP | POLLERR) - client hang up or some error happened */

/* close the corresponding connection socket fd */

if (close(pfds[j].fd) == -1) {

perror("close");

exit(EXIT_FAILURE);

}

--num_open_sockfds;

}

/* */

}

}

It is important to note that this code is still blocking – it blocks on

the poll() socket API call. The difference is, however, that we are not

blocking on a particular socket but rather on a whole set of sockets until at

least one of them has available data (or any other event depending on what you

set for the events field). The socket whose events’ field is not null and

has the bitmask, for instance, POLLIN set is guranteed to instantly return

upon a call to recv().

Now let’s write a multi chat room application where multiple clients could

connect to the same server and send messages to it. Upon reception of a message,

the server sends it back to all other clients. We will only write the server

program since we can simply just use telnet for the clients.

The creation of a listening socket through which connections are accepted is

a common step in every(?) TCP server. We will refactor it into the

sockethelpers library that we have previously created. In the previously

created sockethelpers.hadd the following function declaration:

1

2

/* returns listening socket file descriptor on success and -1 on failure */

int create_listening_socket(const char *port, int backlog);

Now create an implementation file for the library and name it sockethelpers.c

and copy/write the implementation of create_listening_socket into it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

#include "sockethelpers.h"

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netdb.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <poll.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

/* Creates a listening socket that can be used to accept connection requests.

* Returns the created listening socket fd. -1 on error. */

int create_listening_socket(const char *port, int backlog) {

int sfd;

int rv;

struct addrinfo hints, *servinfo, *p;

memset(&hints, 0, sizeof(hints));

hints.ai_family = AF_INET;

hints.ai_socktype = SOCK_STREAM;

hints.ai_flags = AI_PASSIVE;

if (getaddrinfo(NULL, port, &hints, &servinfo) != 0) {

perror("getaddrinfo");

return -1;

}

for (p = servinfo; p != NULL; p = p->ai_next) {

sfd = socket(p->ai_family, p->ai_socktype, p->ai_protocol);

if (sfd == -1)

continue;

/* running this server multiple times, in succession, with small delay

* can cause the "Address already in use" error. Very briefly, the TCP

* socket was left in a TIME_WAIT state - which by default could cause

* an error when a reuse attempt of the socket is made. To "fix" this,

* we set the REUSEADDR socket layer option (if you really want to get

* an idea why I put fix between quotes then read this absolutely

* gorgeous article here:

*

* https://vincent.bernat.ch/en/blog/2014-tcp-time-wait-state-linux)

*/

int y = 1;

if (setsockopt(sfd, SOL_SOCKET, SO_REUSEADDR, &y, sizeof(int)) == -1) {

close(sfd);

perror("setsockopt");

continue;

}

if (bind(sfd, p->ai_addr, p->ai_addrlen) == 0)

break; /* success */

close(sfd);

perror("bind");

}

freeaddrinfo(servinfo);

if (p == NULL) {

return -1;

}

if (listen(sfd, backlog) == -1) {

close(sfd);

perror("listen");

return -1;

}

return sfd;

}

Now create a new multichatserver.c file and copy the following write/code into

it (as usual - pay attention to the comments and the general skeleton

surrounding poll):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

#include "sockethelpers.h"

#include <arpa/inet.h>

#include <netdb.h>

#include <netinet/in.h>

#include <poll.h>

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/socket.h>

#include <sys/types.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#define MAX_CLIENT_MSG_LENGTH 256

/* Sends a message to all recipients in provided pfds set except to the

* except_fd and listener_fd sockets. */

void broadcast_msg(const struct pollfd *pfds, int fd_count, const char *buf,

size_t buf_len, int listener_fd, int except_fd) {

for (int i = 0; i < fd_count; ++i) { /* send the message to all others */

int dest_fd = pfds[i].fd;

if (dest_fd != listener_fd &&

dest_fd != except_fd /* without this an inifinte loop occurs */) {

if (send(dest_fd, buf, buf_len, 0) == -1) {

perror("send");

}

}

}

/* and print the sent message to this server's stdout */

printf("%s", buf);

}

/* Add a new entry to pfds with POLLIN bit set in events and re-allocates if

* necessary. */

void add_to_pfds(struct pollfd **pfds, nfds_t *pfds_count,

nfds_t *pfds_capacity, int newfd) {

if (*pfds_count == *pfds_capacity) { /* no more space left - reallocation */

*pfds_capacity *= 2; /* double the capacity */

*pfds = (struct pollfd *)reallocarray(*pfds, (*pfds_capacity),

sizeof(struct pollfd));

}

(*pfds)[*pfds_count].fd = newfd;

(*pfds)[*pfds_count].events = POLLIN;

(*pfds)[*pfds_count].revents = 0; /* make sure to 0 initialize this because it

could be that add_to_pfds is called within a loop over pfds */

++(*pfds_count);

}

/* Closes and replace the socket fd at provided index from the pfds array

* with the last element. */

void del_from_pfds(struct pollfd *pfds, nfds_t *pfds_count, int *idx) {

close(pfds[*idx].fd);

pfds[*idx] =

pfds[*pfds_count - 1]; /* now idx holds the previously-last elem */

--(*pfds_count);

--(*idx);

}

/* Handles a new connection by calling accept, performing error checks, and

* adding the new connected socket (client) to pfds. */

void handle_new_connection(struct pollfd **pfds, nfds_t *pfds_count,

nfds_t *pfds_capacity, int listenerfd) {

struct sockaddr_storage remoteaddr;

socklen_t addrlen;

int newfd;

char remoteIP[INET6_ADDRSTRLEN];

addrlen = sizeof remoteaddr;

newfd = accept(listenerfd, (struct sockaddr *)&remoteaddr, &addrlen);

if (newfd == -1) {

perror("accept");

} else {

add_to_pfds(pfds, pfds_count, pfds_capacity, newfd);

/* broadcast to all clients (except the new client itself) that a new user

* has joined the chat room */

char msg_buf[256];

snprintf(msg_buf, sizeof(msg_buf), "user %d joined the chat room\n", newfd);

broadcast_msg(*pfds, *pfds_count, msg_buf, strlen(msg_buf) + 1, listenerfd,

newfd);

}

}

/* Handles the client data which amounts to either receiving a message and